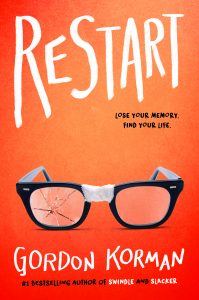

FROM RESTART

CHASE AMBROSE

I remember falling.

At least I think I do. Or maybe that’s just because I know I fell.

The grass is far away – until it isn’t anymore. Somebody screams.

Wait – it’s me.

I brace for impact, but it never comes. Instead, everything just stops. The sun goes out. The world around me disappears. I’m being shut down like a machine.

Does this mean I’m dead?

Blank.

The light is harsh, florescent, painful. I squeeze my eyes shut, but I can’t keep it out. It’s an explosion.

Voices are babbling all around me. You can’t mistake the excitement.

“He’s awake –”

“Get the doctor –”

“They said he’d never –”

“Oh, Chase –”

“Doctor!”

I try to make out who’s there, but the light is killing me. I thrash around, blinking wildly. Everything hurts, especially my neck and left shoulder. Blurry images come into focus. People, standing and sitting in chairs. I’m lying down, a sheet over me –white, which makes the brightness even worse. I raise my hands to cover my face and suddenly I’m tangled in wires and tubing. A clip on my finger is tethered to a beeping machine next to my bed. An IV bag hangs from a pole above it.

“Thank God!” The lady beside me is choked with emotion. I can see her better now – long brown hair, dark-rimmed glasses. “When we found you, lying there –”

That’s all she can manage before she breaks down crying. A much younger guy puts an arm around her.

A white-coated doctor bursts into the room. “Welcome back, Chase!” he exclaims, picking up a chart on a clipboard at the foot of my bed. “How do you feel?”

How do I feel? Like I’ve been punched and kicked over every inch of my body. But that’s not the worst part. How am I supposed to feel when nothing makes sense?

“Where am I?” I demand. “Why am I in a hospital? Who are these people?”

The lady with the glasses gasps.

“Chase, honey,” she says in a nervous voice. “It’s me. Mom.”

Mom. Doesn’t she think I know my own mother? “I’ve never seen you before in my life,” I bluster. “My mother is – my mother is –”

That’s when it happens. I reach back for an image of Mom and come up totally empty. Ditto Dad or home or friends or school or anything. It’s the craziest feeling. I remember how to remember, but when I actually try to do it, there’s nothing. I’m like a computer with its hard drive wiped clean. You can reboot it and the operating system works fine. But when you look for a document or file to open, nothing’s there.

Not even my own name.

“Am I – Chase?” I ask.

While my other questions sent murmurs of shock around my hospital bed, this one is greeted with silent resignation.

My eyes fall on the chart in the doctor’s hands. On the back of the clipboard is written AMBROSE, CHASE.

Who am I?

“A mirror!” I exclaim. “Somebody give me a mirror!”

“Perhaps you’re not ready for that,” the doctor says in a soothing tone.

The last thing I’m in the mood for is to be soothed. “A mirror!” I snap.

The lady who calls herself Mom fumbles inside her pocketbook and hands me a makeup compact.

I open it up, blow away the loose powder, and stare at my reflection.

A stranger stares back at me.

Amnesia. That’s what Dr. Cooperman says I have. Acute retrograde amnesia – the loss of all memory prior to a certain event. In this case, me taking a swan dive off the roof of our house.

“I know what amnesia is,” I tell him. “So how come I remember a random word like that, but I can’t remember my own name? Or my own family? Or why I was climbing on the roof?”

“That I can answer,” supplies the younger guy, who turns out to be my older brother Johnny, a college freshman home for the summer. “Your room has that dormer window. You just open it up and crawl out onto the eaves. You’ve been doing it as long as I can remember.”

“And did anybody warn me I might break my neck?”

“Only since you were six,” my mother puts in. “I figured if you survived this long it was time to stop worrying. You were such an athlete …” Her voice trails off.

“Amnesia can be an unpredictable thing,” the doctor informs us. “Especially with a traumatic injury like this one. We’re just starting to understand which parts of the brain control which life functions, but for all we know, it has nothing to do with geography. Some patients lose long-term memory, some lose short-term memory. Others lose the ability to transfer from short to long-term. In your case, the damage seems totally confined to your sense of who you are and what’s happened in your life up until this point.”

“Lucky me,” I say bitterly.

Cooperman raises an eyebrow. “Don’t knock it. You remember more than you realize. You can walk and talk and swallow and go to the bathroom. How’d you like to have to relearn everything, even how to put one foot in front of the other?”

The bathroom part is definitely an upgrade. They say I was in a coma for four days before I woke up. I can’t say how the bathroom side of things was taken care of during that time, but I’m pretty sure I had nothing to do with it. Maybe I’m better off not knowing.

The doctor checks a few readings on my monitor, making notes on my chart, and then regards me intently. “Are you absolutely certain you can’t remember anything at all from your life before you regained consciousness?”

Once again, I peer back into the nothingness that’s where my memory is supposed to be. It’s like reaching into a pocket for something that should be there but isn’t. Only that something isn’t keys or a phone; it’s your whole life. It’s bewildering and frustrating and terrifying at the same time.

Try harder, I push myself. You didn’t just whoosh into being when you came out of that coma. You’re in there somewhere …

A vague image starts to form, so I bear down, concentrating with all my might, trying to wrestle it into focus.

“What is it?” Johnny asks breathlessly.

At last the details sharpen into view. I see a little girl, maybe four years old, wearing a blue dress with white lace. She seems to be standing in some kind of garden – at least, she’s surrounded by greenery.

“Well, there’s this girl –” I begin, struggling to keep the picture in my head.

“Girl?” Cooperman turns to my mother. “Does Chase have a girlfriend?”

“I don’t think so,” Mom replies.

“It isn’t like that,” I insist. “This is a little kid.”

“Helene?” my mother asks.

The name means nothing to me. “Who’s Helene?”

“Dad’s kid,” Johnny supplies. “Our half sister.”

Dad. Sister. I search for a connection between these words and the memories they should trigger. My mind is a black hole. There might be a lot in there, but it can’t get out.

“Are the two of them close?” Cooperman inquires.

Mom makes a face. “Doctor, after the accident, my ex-husband came to shout and accuse and punch the emergency room wall. Have you seen him here since then, while his son lay in a coma? That should give you an idea of the relationship between my boys and their father and his new family.”

“I don’t know any Helene,” I volunteer. “But you can’t go by me because I don’t know anybody. This is just a little blond girl in a blue dress with white lace. Kind of dressed up, like maybe she’s going to church or something. But why I remember her and nothing else, I can’t tell you.”

“Definitely not Helene,” Mom concludes. “She has dark hair like her mother.”

I turn to the doctor. “Am I just crazy?”

“Of course not,” he replies. “In fact, this little blond girl suggests that your memory isn’t gone at all. It’s only your ability to access it that’s been damaged. I believe that your missing life will come back to you – or at least some of it will. This girl might be the key. I want you to keep thinking about her – who she is, and why she’s so important that you remember her when everything else has disappeared.”

I honestly try, but there are too many other things going on. Now that I’m not dead, the hospital is suddenly in a big hurry to get me out of there. Dr. Cooperman runs tests on every part of me except my left earlobe. Turns out my brain may be short-circuited but the rest of me still works.

“So how come I ache all over?”

“Muscular,” is his diagnosis. “From the fall. Or should I say –” He chuckles at his own joke – “the sudden stop at the bottom. Every muscle from nose to toes tenses up from that kind of shock. Tack on ninety-six hours of complete inactivity, and you stiffen all over. It’s normal. It’ll pass.”

My only real injuries are a concussion and a separated left shoulder. Turns out my bad diving form saved my life. My shoulder hit the ground a split second before my head, absorbing just enough of my hard landing to keep the impact from killing me.

Mom brings clothes for me to change into. I suppose I shouldn’t be so blown away that they fit. They’re my clothes, after all — but of course, they’re new to me. I can’t help wondering if I have a favorite shirt, or a super-worked-in pair of jeans.

I don’t remember the car either – a Chevy van. Or the house. I take the opportunity to fill in a few blanks about myself. I am not the child of millionaires. I have no great love of cutting the grass. Or maybe that one’s on Johnny. I’ve got an excuse: I’ve been in a coma.

I note the window I must have climbed out of, since it’s the only one with roof access. For some reason, I expected it to be higher, and I’m embarrassed. Like it’s an insult to my manliness that such a puny fall scrambled my brains.

When Mom opens the door, a chorus of voices cry out, “Surprise!”

A makeshift banner hangs across the living room: WELCOME HOME, CHAMP!

A heavyset man about Mom’s age steps forward, enfolds me in a crushing bear hug, and rubs his knuckles up and down my head. “Good to have you back, son!”

Mom is horrified. “Stop it, Frank! He has a concussion!”

The man – my father? – lets me go, but he’s defiant. “Ambrose men can take a few licks, Tina. You’re talking about an all-county running back.”

“Ex-all-county running back, Dad,” Johnny amends. “You heard the doctor – Chase can’t play football this season.”

“Dopey doctor,” my father snorts. “What does he weigh? One-forty, soaking wet?” He faces Mom. “Don’t turn him into a wimp like you did with Johnny.”

“Thanks, that means a lot,” my brother says drily.

“Why are you here, Frank?” My mother is quickly losing patience. “How many times have I asked you not to use your key anymore? This is not your house, and it hasn’t been for a long while.”

“I pay the mortgage on this place,” he growls. All at once, the cloud lifts from his face, and he’s grinning. “Besides, we had to be here to welcome home the conquering hero.”

“Falling off a roof doesn’t make me a hero,” I mumble. I can’t put my finger on it, but there’s something about my dad that makes me nervous. It isn’t physical. In fact, for a middle-aged guy, he’s pretty energetic and spry, despite the paunch and the thinning hair. His smile is totally overpowering. To see him is to want to like him. Maybe that’s the problem, I decide. He’s too confident that he’s welcome everywhere. And going by Mom, he isn’t. Not here, anyway.

He’s brought his new family – a wife named Corinne, who doesn’t look much older than Johnny, and Helene, my four-year-old half sister. Mom was right – Helene’s definitely not the girl in the blue dress. It’s no big deal, I guess, but I’m disappointed. I was kind of hoping for one thing in my life to be connected to reality.

Although I’m meeting them for the first time, I have to remind myself they already know me. For some reason, they don’t seem to like me very much. Corinne hangs back, and the little kid stays firmly attached to her mom’s skirt. They look at me like I’m a time bomb about to go off in their faces. What did I ever do to them?

My father seems to be settling in for a long visit, but Mom’s having none of that. “He has to rest, Frank,” she says. “Doctor’s orders.”

“What – he’s chopping wood? He’s resting.”

“Alone,” she insists. “In his room. Where it’s quiet.”

He sighs. “Ants at a picnic, that’s what you are.” He hugs me again, squeezing slightly less this time. “Great to have you back, Champ. Sorry it couldn’t be more of a celebration, but Nurse Killjoy over there –” He inclines his head in my mother’s direction.

I stick up for her a little. “She’s right about the doctor. He said I have to take it easy because of my concussion.”

“Concussion,” he snorts. “When I played football, I got my conk bonked plenty of times. You rub a little dirt on it and you’re good to go.”

Corinne appears at her husband’s elbow. “We’re so glad you’re okay, Chase. Come on, Frank. Let’s go.”

For some reason, I feel like I have to fill the hostile silence that follows. So I lean down to my kid sister. “That’s a nice doll you’ve got there. What’s her name?”

She shrinks back like I’m about to eat her.

Eventually, Dad’s gone, taking Corinne and Helene with him. Johnny goes out to meet some friends and Mom orders me upstairs to get a head start on the relaxation that almost caused a civil war.

She has to show me which room is mine, because I don’t remember any of it – not the wooden staircase with the faded floral runner up the center; not the narrow hallway with the low ceiling; not the wooden door with the crack down the center panel.

My mother sees me evaluating the damage and is momentarily surprised by my surprise. Then she tries to explain it away. “That’s probably my fault. I always let you and your friends play sports in the house. You’re too big for that now – or the house is too small.”

“Which sports?” I ask.

Tears are coming to her eyes. This is hard for her.

“Football. Soccer. Badminton. You name it.”

Being in my room is the weirdest experience of all. It’s my room – there’s no question about that. The walls are covered with newspaper clippings about football teams I starred on and lacrosse games I won. That’s me in the pictures, me diving into end zones and being mobbed by ecstatic teammates – more unfamiliar faces. There are trophies too – shelves of them. Big, small, all shiny. Chase Ambrose, Top Scorer; Chase Ambrose, MVP; Most Yards From Scrimmage; Team Captain; State Champions … I’m really somebody!

It takes some doing to screw up my courage, but I eventually make it over to the window. I was wrong before; it’s plenty high. I’m lucky to be alive.

It’s like I’ve been parachuted into the middle of someone else’s life – someone who looks exactly like me, yet isn’t me.

The doctor is right. I need to rest.

I sit down on the edge of the bed – my bed. There’s a phone on the nightstand, the screen cracked. I wonder if I had it with me when I fell.

I press the home button. It’s dead.

There’s a charging cable right beside it, and I plug it in. After a couple of minutes, the display lights up, and there I am again, with two other kids – complete strangers, although you can tell from the pose that the three of us are close friends.

It’s a selfie, with the kid on my right as photographer. I’m in the middle, and the smallest of the three of us, which is surprising, since I’m a pretty big guy. It must be Halloween, because there are little kids in costume in the background. I’m wielding a baseball bat, holding it high. Hanging off the tip of it is a mangled, ruined jack-o-lantern.

The screen goes dark, and I press the button again. The image of the triumphant pumpkin-bashers reappears. I can’t take my eyes off it. All three of us wear wild, gleeful, unholy cake-eating grins.

What kind of person am I?