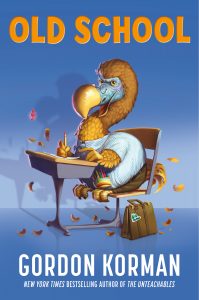

FROM OLD SCHOOL

DEXTER FOREMAN

“G – forty-seven.”

The community room buzzes as the players rush to cover the number on their Bingo cards. I’m practically vibrating in my sneakers. I’m an I-19 away from Bingo!

I glance up to the caller’s table, where the prize jar is well over half full of quarters. This is going to be the biggest payout we’ve had in months! If I win it, that’ll be the cat’s pajamas – which is what they say around here about something really, really great. I’ll be playing for free until I’m thirty.

Cool your jets, I say to myself Bingo is serious business at The Pines Retirement Village. Archie calls it a blood sport – kind of like our Hunger Games. Not that many people here read The Hunger Games or even watch the movies. The Pines is a seniors’ community. You have to be fifty-five just to live here, and most of the residents are a lot older than that. Like Archie, who just turned eighty. Or my grandma – seventy-six. Or my best friend, Leo. He’ll be one hundred next year.

I’m only twelve, but I’m a special case.

“N – forty-four.”

Flurries of movement all around me – discs being placed over squares. Please don’t let me lose now – not when I’m so close!

“Bingo!” calls a shrill voice.

Sudden panic followed by relief. It’s just Miss Wefers. Miss Wefers declares Bingo all the time, but she doesn’t even have a card. She just likes to be a part of things. It doesn’t bother me, but some of the real hardcore players like Archie want her banned from the community room. Grandma would never let that happen. She always says the Bingo players need to get a life. I’m not sure I agree with her on that one. Here at The Pines, Bingo is life.

A few more numbers are called and you can tell by the rising tension in the room that a lot of people are getting really close. I’m still stuck on I-19 and sweating bullets.

“Bingo!”

It’s a double call from opposite sides of the room. There’s a mad dash in two different directions as players rush to verify the winning numbers and make sure there’s no funny business,. During the hustle and bustle, a wayward elbow jostles the quarter jar off the table and it smashes on the tile floor. The noise level jumps to eleven. Old ladies have a lot to say about what to do when there’s broken glass on the floor. This gets a rise out of Archie, who doesn’t appreciate being bossed around.

“We never called B-fourteen! It was B-fifteen!”

“Stay away from the glass with those sandals. You want to get the lockjaw?”

“It was B-fourteen! You need to take that hearing aid back to the Dollar Store!”

“Drop those quarters, Barney!”

“Hey – no fighting in front of the kid!”

The kid – that’s me. People at The Pines don’t agree on much – especially where Bingo is concerned. But they’re on the same page when it comes to me. In a way, they’re all my parents – although grandparents and great-grandparents would be more like it, age-wise. Along with Grandma Adele, they’re raising me together, even though a retirement community isn’t the average place for a kid to grow up.

It’s a real brouhaha, when all at once, total silence falls over the noisy crowd. Every eye turns to the door where my grandmother stands next to the second-youngest person in the community room – a uniformed police officer. Everybody’s pretty cowed. Like, are our Bingo games so rowdy that they have to send the cops to shut us down?

The officer is wide-eyed too, as if he didn’t bring a big enough prison bus to fit forty-seven unruly senior citizens.

Then his eyes fall on me and I realize I’m the one he was looking for the whole time.

“Dexter Foreman?”

“Who wants to know?” Archie asks defiantly.

I’m confused. I’ve lived the past six years with my grandmother in her condo at a retirement community. I’ve never broken a law in my life. What could the police possibly want with a kid like me?

Grandma doesn’t see so well anymore, but she still has the most expressive eyes of anyone I know. Right now, they radiate deep concern.

Something’s up. Something bad.

In the foyer outside the community room, the cop introduces himself as Sergeant Kurtz, truancy officer for the county.

“Where are Dexter’s parents?” he asks Grandma.

“Belgium,” she replies. “Working with the European Union. But I think they’re going to Singapore soon. My daughter-in-law is with the diplomatic corps, so they move around a lot. Dexter has been with me here since he was small.”

I’ve heard the story so many times that I know it by heart. When I was six, Mom was offered a temporary post in Europe, so my folks left me with Grandma for a few months. But Mom wound up a rising star at the State Department and Dad became a big shot in international finance. Oh, we talked about me joining them over there, but they were always so busy that we kept putting it off. I was fitting in great at The Pines, almost the unofficial mascot of the place. And when Grandma’s vision starting going downhill, it kind of became my job to help her out. Before we knew it, I’d lived half my life here. I understand that sounds pretty wonky, but for us, it’s just the way things worked out.

“What’s truancy?” I ask the sergeant.

“I’m in charge of school attendance,” he explains. “It’s come to our attention that – well, you don’t go.”

Grandma speaks up. “Dexter is getting an excellent education right here.”

“Where?” The officer makes a show of checking his surroundings. “There’s no school at The Pines. There’d be no one to go to it except Dexter. The law in Bradford County – and every county, as a matter of fact – states that all children must be educated.”

“I am educated,” I insist. “I mean, not yet, but I’m up to seventh-grade level, which is where I’d be in real school. It’s like home-schooling, only instead of at a house, I get taught by people around here.”

With a babble of angry voices, the Bingo argument in the community room spills over into the foyer. I have to admit it doesn’t sound like a faculty meeting at Harvard, especially when Archie threatens to wring somebody’s “chicken neck.” He can be an excitable guy for an eighty-year-old.

“There are half a dozen retired educators living in the community,” Grandma argues. “Also two college professors and some true experts in their fields. Do you know who teaches Dex English? Phyllis Birdwell, that’s who.”

The officer looks blank. “Who’s Phyllis Birdwell?”

“Only a New York Times bestselling author,” I supply. “And my math teacher is Leo Preminger. He was one of America’s greatest code-breakers back in World War II.”

“Never heard of him,” Sergeant Kurtz admits.

“Well, of course not,” I say. “His work was top secret. He was part of the Bunker Boys, an elite unit of cipher experts operating in Wolf’s Eye. They helped break some of the toughest enemy codes. He’s my best friend.”

“Best friend? What is he – like, ninety?”

“Ninety-nine,” I amend proudly. “He’ll be a hundred in April.”

The officer swallows hard. “School’s going to be good for you. You’ll meet kids your own age.”

“I have friends my own age,” I defend myself. “Teagan Santoro, for one. Her grandparents live here. She visits all the time – a lot of kids do. We mingle.” I can already tell Sergeant Kurtz thinks I’m an oddball for living in a retirement community, so I switch to a kid word. “We chill.”

Teagan’s my best kid friend, even though she lives in New York, which is a two-hour plane ride from here. And we’re pen pals. We write to each other about important things in our lives, like when Teagan told me about getting her first iPhone. She was pretty excited about that. I have Grandma’s old flip-phone, which doesn’t run the new games or apps – or any games or apps, to be honest. Come to think of it, I haven’t heard from Teagan since that time. Maybe her latest letter got lost in the mail. That would make sense because the Post Office is run by the government. Just about everybody at The Pines says the government isn’t fit to run a sewing circle, much less a whole country.

I’m the most comfortable with older people, though. They’re more honest. If their back hurts, they tell you. If a new pill causes dizziness or ringing in the ears or upset stomach, they tell you. They describe exactly how it feels to have a kidney stone or when your son, the Wall Street Big Shot, hardly ever calls anymore. Kids don’t really discuss their lives that way. All they care about is memes, whatever they are.

The truancy office nods. “There’s a lot more chilling in your future. Make sure you’re ready Monday morning, seven-forty sharp. The bus will pick you up at the main gate.”

“There’s no bus at The Pines,” I inform him. “We just have the courtesy shuttle to take people to the mall and doctors’ appointments.”

“Not that bus. The school bus.”

I’m horrified. “You mean Big Orange?” I see them around, but I’ve never actually been in one.

He gives me a reassuring nod. “Haven’t lost a kid yet.”

My grandmother speaks up. “Sergeant, are you sure this is really necessary? Thousands of children are home-schooled. Dex’s situation is no different.”

“I have my orders, ma’am,” the officer replies firmly. “As of Monday, your grandson is a seventh-grader at Wolf’s Eye Middle School.” He turns to me. “When Big Orange pulls up, make sure you’re on it.”

In the community room, they’ve got the game back up. “I – nineteen!” the caller announces.

Bingo.

I lose.

CHAPTER TWO

GIANNA GRECO

Nothing ever happens around here.

Figures. I finally get promoted to reporter at the Wolf’s Eye Middle School newspaper, the Eyeball. After suffering though sixth grade as a go-fer in the print shop – breathing toner up my nose until I sneeze and ruining all my clothes with splatters of ink from spent cartridges – I’ve made it at last. No seventh graders ever make it to the reporting staff. My brother warned me about that. He’s in seventh grade too, but he had to repeat a year, so he’s been here longer. Ronny never worked for the paper – he’s not a joiner. But he’s 100 percent spot on that the eighth graders treat this school like it’s their own private club. The Eyeball editors barely tolerate me. If I expect to survive, I’ll have to blow the doors off the place with a monster story.

And where am I going to get that in a random dot on the map where nothing ever happens?

Wolf’s Eye has to be the most boring place on the face of the earth. We’re too far from the city to be considered the suburbs, but too close to have small-town charm. We’re not near the ocean, not in the mountains, and not in the plains. We’re just sort of here. And our middle school – well, the only interesting thing about that is what a dump it is. The biggest argument in town is whether we should tear it down or just wait for it to collapse on its own. Except new schools are expensive, and people are divided over whether it would be worth it to spend the money or just keep on fixing and patching the old doghouse. We’re not the richest community in the world either.

But from a reporter’s standpoint, the worst thing about middle school life in Wolf’s Eye is how predictable it is. Take this bus ride, for instance. I’ve already memorized every inch of it because nothing ever changes. Left on Mosswood; right on Main. I close my eyes but the route is still implanted on my brain. I feel us navigating the traffic circle and – bump! – there’s the pothole in front of the strip mall.

A few kids board the bus here, but I keep my eyes shut. I already know who they are. Sophie Tanaka. Ethan Benlevi. And Jackson Sharpe – yup, I can hear the high-fiving. Wherever Jackson goes, he moves through a storm of backslaps, handshakes, and fist-bumps. If he wasn’t so full of himself, I’d actually admire him. He’s the rare middle school big man on campus who’s as good in the classroom as he is on the sports field – athlete and mathlete, rolled into one. Even Ronny likes Jackson, and Ronny hates everybody. Anyway, I don’t have to admire him. He admires himself enough for both of us.

I hear the sound of the door folding closed and we’re on the road again. Two more pickups; full stop at the railway crossing; and then straight on –

When the school bus roars into a wide left turn, I’m so caught off guard that I almost fall out of my seat. Grabbing hold of the bench in front of me, I open my eyes. We’re heading down a narrow tree-lined road that is definitely not on our route. Are we being kidnapped? Okay, that would be bad, but at least I’d have something to write about in the Eyeball. BUSLOAD OF KIDS HELD FOR RANSOM. Or maybe PARATROOPERS ARREST BUS-JACKERS IN DARING RESCUE. Or even SOMETHING FINALLY HAPPENS IN WOLF’S EYE; ENTIRE TOWN DIES OF SHOCK.

“Where are we going, Mr. Milinkovic?” Sophie calls.

At least I’m not the only one who knows this route so well that the slightest deviation sets off alarm bells.

“New pickup,” the driver tosses over his shoulder.

Now everyone on the bus is paying attention. Something new happening in this town is so rare that the last thing you want to do is blink and miss it.

We drive along a low stucco wall, draped with ivy. Beyond it, I can make out small houses and low apartment buildings. It seems to be a condo complex – although I don’t know this neighborhood very well.

That’s when I see the sign:

THE PINES

A COMMUNITY FOR SENIORS

We pull up to the main gate, where a group of about ten people stands waiting for us. But here’s the thing: They’re all old! Gray hair, bald heads, canes, walkers. Not that there’s anything wrong with being elderly, but what do they want with us? We’re the bus to the middle school. The youngest member of this crowd would be going into the eightieth grade!

“Check out the geezer squad,” Ronny comments from the back. That’s another thing about my brother: he’s always got something to say – usually something not very nice.

“Now we know where Santa hangs out when it’s not Christmas,” Jackson adds with a snicker.

Then one kid steps forward. He’s about our age, pretty tall and kind of round-shouldered, with very short medium brown hair in almost a military cut. Instead of a backpack, he’s carrying a fancy briefcase – the kind lawyers and business executives use. He’s obviously the center of attention among the old folks. The ladies hug him and fuss over him and the men all shake his hand. The way everybody’s acting, you’d think he was setting off on a six-month world tour.

Nobody pays any attention to Mr. Milinkovic, who says, “Got a schedule to keep, folks.”

Then the new kid is climbing up the steps onto the bus. The first thing I notice is he’s dressed all wrong. His pants look like suit pants, but not narrow and tailored, pressed with a crease. These are baggy with cuffs at the bottom, and sitting like drapery atop gigantic white sneakers. The waist is too high, secured by a tan belt roughly ten sizes too big. He looks like a scarecrow, cinched around the middle.

His collared shirt is tucked in. Like the shoes, it’s whiter than white. In the pocket is a plastic protector with a lineup of pencils and pens. He wears a heavy cardigan over that, even though the temperature is supposed to hit seventy-five today. The whole outfit comes together like a bad orchestra falling into clashing discord. It’s not that his clothes don’t fit. They almost do. But the pants are too long, the shirtsleeves are too short, and the collar hangs limp even though it’s buttoned all the way to the top.

A murmur begins to ripple up and down the aisle – a not-too-nice one that includes words like nerd and geek and weirdo. I’m not a fan of judging people by their appearance, but even I have to ask myself what is this new guy trying to prove? He must know it’s not Halloween. Doesn’t he realize how odd he looks?

The doors close and the bus pulls away from The Pines. The elderly farewell committee stands waving. One slight, gray-haired lady is dabbing at tears with a handkerchief.

Walking gingerly in the moving vehicle, the new guy makes his unsteady way to an empty row and eases himself into the seat.

I pick myself up and sit down on the bench beside him. “Hi, I’m Gianna.”

“Dex.” The expression on his face: one hundred percent misery. Well, maybe ninety-five. The other five percent: ticked off. He doesn’t want to be here.

“Yeah, I get it,” I tell him sympathetically. “It’s tough to be new, especially in a town like Wolf’s Eye. Most of the kids here have been in school together since kindergarten. Where did you move from?”

“I’ve lived here my whole life.”

“Really?” I ask. “Did you go to private school before this?”

He shakes his head. “I was home-schooled. By Leo and Phyllis and Cyril and …”

Dex rattles off a few more names that don’t ring a bell. “I don’t know those kids,” I admit. “Are they in the high school?”

“You just saw them,” he says a little impatiently.

“You mean the old people?” I blurt.

“They’re my friends,” he insists. “And one of them is my grandmother. I’ve been living with her in the condo for more than half my life.”

I can feel my eyes widening at the story he goes on to tell. Dexter Foreman is a seventh grader like me, but when he was six, his parents took off on this international jet-set lifestyle, leaving Dex with his grandmother to grow up in her retirement village. I have a sudden flash of understanding about his clothes, which are so strange, yet also strangely familiar. He dresses like my grandfather! Bits and pieces from once-snazzy outfits that are semi-retired. High waists; big clunky shoes designed for sore feet. A sweater because you never know when there’s going to be a draft. This kid is twelve years old going on eighty!

Approaching a red light, the bus downshifts in a shriek-grinding of gears and brakes. Dex grabs the seatback in front of him, holding on with white knuckles and closed eyes.

I stare at him. “Haven’t you ever been on a school bus before?”

He’s exasperated. “Why would I go on a school bus if I don’t go to a school?”

“So why did you decide to switch from home-schooling to the real thing?” I probe.

He heaves a heavy sigh. “I didn’t. The truancy officer made me.”

“Truancy?” I have an instinct – a reporter’s instinct. It buzzes when I sense there’s a story to be told. Right now, it’s vibrating like a guitar string. “It’s not truant to be home-schooled. Thousands of kids do it every day.”

“I’m not officially home-schooled,” he mumbles, embarrassed.

“What do you mean, officially?”

“My grandma didn’t want to fill out all the paperwork to have a kid living in a seniors community,” he explains. “So she put that I was sixty instead of six. And Bradford County never registered me for school because they thought I was too old.”

I sit forward. “And how did they find out you were our age?”

He makes a face. “According to county records, I turned sixty-five and they followed up to see why I never applied for social security.”

“And they realized you’ve never been to school,” I conclude. This story would be hilarious if it wasn’t making him so sad – some county bureaucrat asking why a senior citizen isn’t on social security and the answer is he’s really twelve.

“That’s what you get when you let the government snoop into people’s private business,” Dex complains.

That’s another old-person thing – blaming everything on the government. In my family, you normally have to wait till Thanksgiving dinner for that. Not anymore.

Suddenly, Dex slaps at the back of his neck. “Ow!”

A tiny object drops onto the seat behind him – a paperclip bent into a C-shape. I recognize it as standard middle-school ammo. All it takes is a rubber band to launch these things with deadly accuracy at some unsuspecting new guy.

I stand up and glare accusingly at the rows behind us. “Real mature, you guys. Who did it?”

Blank looks, except for one. My brother is cackling into the crook of his arm. Real subtle.

“Cut it out, Ronny,” I snap.

He responds with his trademark shrug, which brings his shoulders up to his stick-out ears. The shrug suggests innocence, but the sneering grin that comes with it confirms that he’s one thousand percent guilty.

Poor Dex, I think to myself as I sit down again. He hasn’t even set foot in school yet and he’s already caught Ronny’s attention.

Yet, even as I’m thinking it, I feel my mouth forming into a smile. I woke up this morning a reporter with nothing to write about. But now the greatest story in Eyeball history has just landed right in my lap. Can a kid who’s never been to school and spent his entire life surrounded by senior citizens survive at Wolf’s Eye Middle School?

I wonder if they give Pulitzer Prizes to seventh-grade reporters.