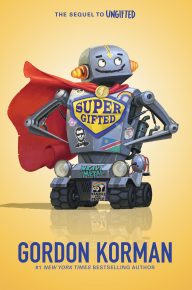

FROM SUPERGIFTED

SUPER-STOKED

NOAH YOUKILIS

I used to go to the Academy for Scholastic Distinction, the top-rated gifted school in the state. According to Oz, my homeroom teacher, I had the highest IQ any of the faculty had ever come across. They held weekly staff meetings on how to keep me stimulated and challenged. They even sent a group of teachers to a conference in Switzerland on how to motivate students at the highest rung of the intelligence ladder.

I was bored out of my mind.

I once saw this video on YouTube where a kid was complaining about a classmate being a know-it-all, and I was amazed at how insensitive that was. It’s no fun to be a know-it-all, because you know it all. You can never be surprised, or shocked, or scared, or thrilled. Because whatever happens, you already saw it coming. Know-it-alls shouldn’t annoy people; everybody should feel sorry for us, and relieved they don’t have this problem.

My teachers at the Academy threw the hardest stuff in the world at me and I threw it right back at them. And none of it challenged me as much as one soufflé in Home and Careers at regular school.

My project was a triumph of data mining, distilling centuries of recipes into a list of ingredients no single chef could have come up with – things like cardamom, and quail eggs, camel’s milk, and finely-ground roasted durian seed. Scientifically, this should have been the most magnificent soufflé in the history of cooking. Instead, it burned like napalm. The fire chief commented that he hadn’t smelled anything like that since the great fertilizer factory explosion of 2006.

My teacher, Mrs. Vezina, said, “You must be very disappointed, Noah.”

How could I ever explain it to her? I wasn’t disappointed; I was stoked! If I was bad at one thing, logic dictated that I could be bad at other things too. It was like discovering a whole new world.

There was an old song from the 1960’s called Be True To Your School that always perplexed me. Why would anyone form a sentimental attachment to a building? There was nothing to be true to except bricks and mortar and glass and a few dozen other materials. But now I was starting to feel real affection for Hardcastle Middle School. It had to be the greatest school in the history of education. It was teaching me how to learn, when, before that, I didn’t need to because I already knew it all.

Some days, the learning started even before I arrived at school. Like this morning, I was on the bus, when, at the stop after mine, this big guy got on, lumbered down to me, and said, “Hey, kid. This seat’s taken.”

“Of course it’s taken,” I agreed. “I’m sitting in it. But there’s a vacant seat next to me. Feel free to use it.”

“Beat it, nerd!” He picked me up by the collar and tossed me across the aisle. A moment later, my book bag slammed into my chest.

I was about to protest the rough treatment when I realized something: In my old seat, the window was open, and it was quite chilly outside. It wasn’t a problem for him. He was a bigger, hardier person. So he wasn’t being mean. He was doing me a favor.

When we were getting off the bus at school, I thanked him for his thoughtfulness. He stared at me and then looked up at the sky. So it was about the weather, as I’d suspected.

The social world at real school could be tricky to understand. But the people were really nice, if only you took the time to understand them.

I still went to the Academy part-time. Donovan and I traveled together by mini-bus for robotics. But I wasn’t that into it. Heavy Metal was a good robot, but any machine was, by definition, predictable. Every line of code in its computer software could be broken down; its hydraulic, pneumatic, and mechanical systems could be analyzed and understood. Any operation that didn’t go exactly according to design could be traced to a specific malfunction – one that could be corrected and repaired. It was the opposite of YouTube, where, if you click on a video, you might get a kid on a pogo stick, or a rocket launch at Cape Canaveral, or some guy playing the piccolo with his nose, or anything at all.

The best part of Heavy Metal was on the lower portion of the main body, just below the left lifting arm. I put it there myself. It’s a picture of Tina Patterson taken at the hospital when she was only three hours old. Normally, Donovan was in charge of decorating our robot with images downloaded from the Internet. So far, he had the flag of Namibia, an Imperial Snow Walker, and a small poster that said: PANDAS ARE PEOPLE TOO. But my picture was better because nothing about Tina could ever be bad. And not even YouTube was as unpredictable as baby Tina. You never knew in advance if she was going to smile, scream, pass gas, gurgle, or spit up all over you. No one could be a know-it-all about Tina, not even me. She was a universal mystery, but that was okay. Whatever she did do, it was fine because her mom let me hold her. A lot.

In a way, Hardcastle Middle School was just as unpredictable as Tina, which was why I liked it so much. It was a lot more crowded than the Academy, so the hallways were chaotic, especially for a short person like me. That was another example of how the Academy, which was supposed to be so challenging, was much easier than here. Just getting from room to room without being elbowed, stepped on, or slammed into a wall was a learning experience. Sometimes Donovan or one of those two guys named Daniel would walk with me. That was something else I never had before – friends.

My favorite class – one that the Academy didn’t offer – was Gym. Of all the subjects where I had room for improvement, it was number one – even more than Cooking. All Phys. Ed classes were held in the old cafeteria, since the gymnasium we shared with Hardcastle High was being renovated after part of a broken statue bowled into it.

Gym had to be the happiest class in the whole school, always ringing with laughter – mostly when I tried to perform some physical skill. Except Donovan, come to think of it. He was always arguing with one of the guys, or jumping in front of me, especially when we played dodge ball. Donovan was a terrible dodge ball player. He was constantly getting hit. Even when he’d already been eliminated, he would hurl himself between the ball and me, getting yelled at by players and earning lots of detentions from Coach Franco.

“You know, Donovan,” I advised, trying to give back some of the loyalty and support I’d received from him since arriving here, “you really ought to chill out.” That was one of his expressions. “And maybe you should practice dodge ball skills in your spare time. You’re black and blue. Look at me. I didn’t get hit once.”

He clenched and unclenched his fists, which didn’t seem like chilling out as I understood the term. Or maybe he was focusing on searching for my pants, which was kind of a Gym class tradition. Whoever was picked last when we chose up teams got his pants hidden. I was really looking forward to the time when I could be in on the hiding part, and not the finding at the end.

People were definitely different here compared to the Academy kids – louder, rougher, sometimes meaner. But I preferred it. People lived their lives here, instead of obsessing over grades or prizes or internships or getting into Stanford or Yale. You heard the phrase “Who cares?” at least fifty times a day. And a lot of those “Who cares?” kids had better grades than I did. What a thrill that was.

I was getting so good at mediocre academic performance that I was called to see Mrs. Ibrahimovic, my guidance counselor. She launched into a speech about how I had to try harder and attend extra help sessions because I was on the verge of failing some of my classes.

I got so emotional that I teared up. In my wildest dreams I never could have hoped that I, Noah Youkilis, would one day be in danger of flunking a subject.

“There’s no need to cry,” Mrs. Ibrahimavic said quickly. “There’s still plenty of time before the end of the year. Don’t give up hope.”

I nodded, but I was still too emotional to manage any words.

“It’s going to be all right,” she soothed. “We’ll get you the support you need. Let me take a look at the transcripts from your last school.” She sifted through my folder and frowned at my records from the Academy, which told of my 206 IQ, my 100% average, and the scholarship offer I received from Princeton on my tenth birthday. “Well, this can’t be right,” she decided, and put the file away. “Now listen, Noah, there’s nothing to be so upset about. We’ll put together a personalized study plan for you, and maybe consider some remedial classes.”

I walked out of that office feeling ten feet tall.

Humming Be True to Your School under my breath, I paused in front of the big bulletin board outside guidance. What an awesome place this was! At the Academy, there wasn’t a single extracurricular activity that I wouldn’t automatically have been number one at. Everything was different here. There was a golf team; a group that made quilts for residents of the local assisted living home; kids who volunteered at the animal shelter; a synchronized swimming club, rock climbers; coin collectors; a bluegrass band; it went on and on.

Giddy from my meeting with Mrs. Ibrahimavic, I felt an urge to join absolutely everything. But that was impossible. There weren’t enough hours in the day.

My eyes fell on the very last poster on the board.

CALLING ALL DANCERS

THE LACROSSE TEAM NEEDS CHEERLEADERS

CAN YOU BUST A MOVE AND RAISE THE ROOF?

SCHOOL SPIRIT! EXERCISE! FUN!

SUPPORT OUR HARDCASTLE HORNETS

SIGN UP HERE

As soon as I saw it, I knew it was tailor-made for me. It was the words school spirit that put it over the top. Be true to your school. That’s what I wanted to do – show this fantastic institution of learning how grateful I was for the opportunities it was giving me. And what better way to do that than by pledging my body and heart to supporting one of the sports teams.

As I signed my name on the dotted line, I’d never felt better about anything in my life.

Head held high, I started for the computer lab in the library. I didn’t know anything about being a cheerleader, but I was sure there was a lot about it on YouTube.

In the hall, I passed Donovan.

“Hi, Noah,” he said absently. Then he wheeled and grabbed my arm from behind. “Wait a minute, I don’t like that look on your face. What are you up to?”

“I thought this year couldn’t get any better,” I told him. “How wrong a guy can be.”