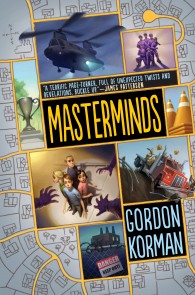

FROM MASTERMINDS

CHAPTER ONE

ELI FRIEDEN

I lie against the cool stone of the pool deck and peer into the filter opening. I can just make out the tip of the boomerang, but I can’t quite jam my hand in deep enough to get a grip on it. “No good.”

“Just our luck,” Randy groans. “I mean, what are the odds? You could throw that thing fifty thousand times and never get anywhere near the filter. But one little challenge, and bulls-eye.”

Randy’s famous around Serenity for his “challenges,” which usually involve catching something uncatchable while riding a bicycle or pogo-stick, swinging on a rope, or rolling inside a truck tire. As his best friend, I’m usually the guinea pig – translation: sucker – for Randy’s cockamamie ideas. Like today’s challenge: Randy throws the boomerang out the window of the treehouse and I’m supposed to leap off the diving board, snatch it out of midair, and do a cannonball into the pool. Only I miss, the cannonball turns into more of a belly-flop, and the boomerang disappears inside the filter.

“Maybe Mr. Amani can get it out,” I suggest. He’s the local handyman, which includes pool maintenance and just about everything else from plumbing and electrical work to ridding your crawlspace of scorpions and baby armadillos.

“And maybe he can’t, which means my folks will have to call the pool guys.”

That’s a much bigger deal than it sounds like. There’s no pool company in Serenity, and the nearest town is eighty miles away. It can take weeks to get anybody to schedule a trip out here, and in the meantime your pool turns to soup. Mr. and Mrs. Hardaway aren’t going to be thrilled with this – although they’re pretty used to it, having dealt with Randy for thirteen years.

We’re accustomed to the occasional inconvenience, though. It’s one of the rare drawbacks to growing up in the community with the best standard of living in the country, according to the study they reported in the Pax, our local paper. Serenity has zero crime, zero unemployment, zero poverty, and zero homelessness. There are only 185 people in town, so it’s a simple matter to make sure all of them have someplace to live. As for jobs, we’ve got the Serenity Plastics Works, one of the largest producers of orange traffic cones in the United States. Our school has the highest test scores in New Mexico. We’re right on the edge of Carson Nation Forest, surrounded by canyons, foothills, and woods, and the sun shines practically every day. True, it gets pretty hot sometimes, but we don’t bake like they do in those real desert towns. Our parents are constantly reminding us how lucky we are to be growing up here, and it’s easy to agree.

But right now, the pool filter is busted, and the nearest repair is in Taos. Randy makes an executive decision. “I’m not going to tell my folks about it. I’ll just act ten times as amazed as everybody else when they find the boomerang in there.”

I’m a little uncomfortable. That’s kind of like lying, and we’ve all learned in school that honesty isn’t just the best policy; it’s the only one. Sure, you hear that on TV and read about it in books. But in Serenity, we live it. It’s one of the reasons why this place so special.

“We could go to my pool,” I suggest, anxious to change the subject. “No boomerang, though.” My dad is twenty times as strict as the Hardaways. He’s the school principal and also the mayor. That’s not much of a job for such a small town. His mayoral salary is a dollar a year, and he always insists that he’s overpaid.

“Nah, I’m sick of swimming.”

“We could hang out in the treehouse.”

“Boring,” he declares. “Every kid in town has a treehouse and none of them are any fun. And don’t say video games either. It doesn’t matter how good your home theatre is when all your games are lame.”

“Our games aren’t so lame,” I remind him. Randy and I have figured out a way to tweak the game software to unlock hidden features, like cars crashing and fighting with real weapons. Turns out I’ve got a knack for that kind of thing. I can do it with my iPad and computers too. It’s strictly hush-hush, because everybody in Serenity is anti-violence. I am, too, but in a video game, where’s the harm in it? It’s not like it’s happening in real life.

“Yawn.” Randy gets this way sometimes, where nothing satisfies him. Basically, he’s a crab. Believe it or not, it’s one of the main reasons I like him. You don’t hear much complaining in Serenity. Randy always manages to find something, though. It’s almost as if he’s daring the universe to do a better job, no matter how great things already are. I think my dad would be happier if I found a different best friend. But let’s face it, in a town with only thirty kids, there’s not much to choose from. And anyway, you don’t find best friends. Best friends just happen.

“So what are we going to do?” I ask him.

“Let’s get out of here. Let’s go somewhere.”

I brighten. “They’ve built that new high slide at the park.”

He’s unimpressed. “Big deal. You climb up so you can come down. Let’s do something cool.”

“Like what?”

“Like –” His eyes dance. “The most awesome old sports car you’ve ever seen.”

“Sports car?” I echo. When you live in a place this small, not only do you know every car; you could probably recite the license plate numbers by heart. When somebody gets a new vehicle, three-quarters of the town shows up to see it. There are plenty of fancy SUVs and sedans, but no sports cars.

“It was the weirdest thing. My dad and I were hiking a few miles out of town and we found an old, abandoned ranch – busted up fences and a house that was nothing but a pile of toothpicks. The only thing standing was this rusted Quonset hut. And when we went inside, the car was there. The tires were flat, and the whole thing was buried in dust and spider webs, but it was beautiful. My dad said it was Italian – an Alfa Romeo. It had Colorado license plates from 1961.”

“Wow,” I say.

“Yeah,” he enthuses. “Let’s go see it.”

“What – right now?”

Randy shrugs. “What are you waiting for – Christmas? It’s not too far. Grab your bike and let’s go.”

I hesitate. “I have to ask my dad.”

He looks pained. “Bad idea. I know your dad.”

Felix Frieden is kind of a joke among the kids in town, with his three-piece suits, and his shined shoes, and his no-nonsense attitude. I always want to stand up for him, but how can I? They’re 100% right. If you put my father in a clown suit, the first thing he’d do would be to have his red plastic nose spit-shined. “You think he’ll say no?”

“Why give him the chance?” Randy insists. “The car’s only a few miles away. We’ll be there and back before he even knows you’re gone. Come on, Eli, live a little.”

“It’s just –” I’m embarrassed to say it, but I have to be honest. “I’ve never been out of town.”

“Neither have I – not since we visited my Grandma when I was six –”

“No,” I interrupt. “I’ve never been anywhere out of town. Not even where your dad took you hiking.”

“What about that time in science when our class went fossil hunting?” he challenges.

“That was still inside the town limits. Mrs. Laska said so.”

He’s amazed. “But haven’t you ever passed that stupid sign – the one that says: Now Leaving Serenity – America’s Ideal Community?”

I shake my head. “I’ve never even seen it.”

“Well, you’re going to see it today,” he decides. “Grab your bike.”

That’s another thing about Randy. He won’t take no for an answer. He doesn’t exactly bring out the best in me, yet he does bring out me – or at least the me that I’d like to be. He does the things I only daydream about, but don’t have the guts to try.

Until today.

Only one road passes through Serenity, a two-lane paved ribbon everybody calls Old County Six. We pedal west along it, riding right down the center over the faded broken line. There’s little fear of meeting traffic in either direction. All decent highways cross New Mexico well to the south. If you hit Serenity, chances are you’re lost.

As we bike on, I spot the gully that was the site of the fossil hunting trip. I am now farther from home than I’ve ever been in my life. Can it really be this easy? You just jump on a bicycle and ride out of town? It seems like cheating somehow, breaking some overarching Law of the Way Things Are Supposed to Be. Yet here I am, just doing it. It’s kind of exhilarating – at least, I’ve never been so aware of the beating of my heart and the blood pumping through my veins.

I feel a little strange about not telling Dad. Not that I need his permission – I’m thirteen years old. Besides, he never specifically said not to ride my bike out past the town limits. I’m not breaking any rules, but I know he’ll be disappointed if he finds out about this. In school, they taught us that lying to yourself is the worst kind of lying. Face it: If I don’t need to ask permission for this ride, how come I snuck my bike out of the garage? I obviously suspected that Dad would give me a hard time about it.

That’s Dad’s problem, not mine, but he’s really good at making it mine. It’s the first thing you learn in principal school: the customer is always wrong. Felix Frieden has elevated guilting to the level of fine art.

I glance over my shoulder at Serenity – the perfect rows of immaculate white homes, the swimming pools positioned on the lots like aquamarine postage stamps, the basketball hoops lined up like sentries, all lovingly set down amid the striking southwestern landscape. In this view I find my answer to the nagging question of how a person could spend thirteen years here without ever once setting foot outside the town proper. Why would I need to? Our town has everything – comfort, security, luxury, recreation, and education – not to mention honesty, harmony, and contentment, the three Essential Qualities of Serenity Citizens. We’ve all heard about the bigger towns and – even worse – cities. They’re awash in garbage and crumbling roads and buildings, and crime is so bad that nobody can trust anybody else. People spend their time in fear, hunkered down behind locked doors and alarm systems.

At the same time, it’s almost startling how nothing the town is, even from this distance of barely a mile. If it wasn’t for the factory, you wouldn’t notice it unless you knew what to look for. I guess that’s the Serenity Miracle our parents are always talking about – that so much quality of life can be held in such a small package.

“How much farther?” I call ahead to Randy.

“Probably another twenty minutes.”

After a bend in the road, a tall butte obscures the town altogether. It completes the feeling of being out there.

Randy doesn’t seem to notice at all. “Look!” he shouts back at me, waving his arm to the right.

It’s the sign Randy mentioned – the one about leaving town. In contrast to spotless and impeccable Serenity, it’s surprisingly faded and weather-beaten. I squint at the bottom, where the warning: No Gas Next 78 Miles has been tacked on.

I’ve done it. I’ve left town. I survey the rocky hills and scrub pines and brush. I don’t know what to call this, but it’s not Serenity anymore. After more than thirteen years, I’m officially Somewhere Else. And how does it make me feel?

To be honest, kind of scared. I’ve never done this before, never lost visual contact with my hometown. By the time I get to see this Alfa Romeo, I’ll be so stressed out that I won’t even be able to appreciate it. I’m over-thinking this whole business to the point where it’s making me sick to my stomach.

Well, I’m not turning back. I made it this far, and I’m going to see it through!

But I really am sick – and getting sicker. The nausea grows stronger, rising up the back of my throat. There’s no way it’s just from being nervous. This is something physical. What did I have for lunch today? I can’t remember, but whatever it was, it’s coming up, and soon. My stomach twists in a paralyzing cramp, and my head hurts too.

“What’s with you, Eli?” Randy calls back in annoyance. “Running out of gas already?”

I’ve slowed down, although I hardly notice it. Only pure stubbornness keeps my legs pumping. I’m in agony, blinded by the kind of headache that lodges behind the eyes like a glowing coal, pulsating and doubling in intensity. The pain is unimaginable. It’s not just a terrible thing; it’s the only thing.

I’m not even aware of toppling off the bike until my chin strikes the road. Fire erupts on my forearms where they scrape the rough pavement. I see Randy kneeling over me, feel him shaking me, but I’m powerless to respond. I can only focus on one thought:

I’m dying.

What happens next is so shocking, so bizarre, that I’m sure I’m imagining it, delirious with pain. A loud, rhythmic roar swells around Randy and me, and strong winds whip down on us. A dark shadow moves directly overhead, growing larger and larger as it descends. An enormous military-style helicopter settles on the road, its rotor buffeting us with air.

The hatch opens and out jump six men in identical indigo uniforms and wine-colored berets.

“Purple People Eaters!” Randy breathes.

Through a fog, I can barely make out the distinctive tunics of the Surety, the security force of the Serenity Plastic Works that doubles as the town police. It takes all the strength I have left to spread my arms to the rescuers.

“Help me,” I whisper, wondering if they can even hear me over the thunder of the chopper.